BOTANY FOR YOUNG PEOPLE AND COMMON SCHOOLS

How Plants Grow

A Simple Introduction to Structural Botany

by Asa Gray

Originally published in 1858 and now in the public domain.

CHAPTER II.

HOW PLANTS ARE PROPAGATED OR MULTIPLIED IN NUMBERS.

SECTION III. -- Flowers (page 2 of 3).

1. Their Arrangement on the Stem. CLICK HERE

§ 2. Forms and Kinds of Flowers.

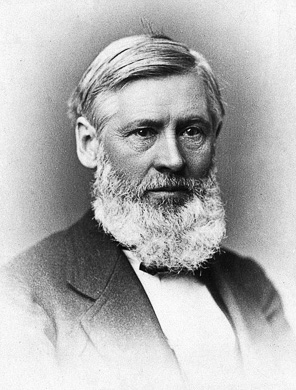

191. The Parts of a Flower were illustrated at the beginning of the book, in Chapter I, Section I. Let us glance at them again, taking a different flower for the example, namely, that of the Three-leaved Stonecrop.

Although small, this has all the parts very distinct and regular. Fig. 153 is a moderately enlarged view of one of the middle or earliest flowers of this Stonecrop. (The others are like it, only with their parts in fours instead of fives.) And Fig.154 shows two parts of each sort, one on each side, more magnified, and separated from the end of the flower-stalk (or Receptacle), but standing in their natural position, namely, below or outside a Sepal, or leaf of the Calyx; then a Petal, or leaf of the Corolla; then a Stamen; then a Pistil.

192. This is a complete and regular, yet simple flower and will serve as a pattern, with which a great variety of flowers may be compared.

193. When we wish to designate the leaves of the blossom by one word, we call them the Perianth. This name is formed of two Greek words meaning "around the flower." It is convenient to use in cases where (as in the Lilies, illustrated on the first page) we are not sure at first view whether the leaves of the flower are calyx or corolla, or both.

194. A Petal is sometimes to be distinguished into two parts, its Blade, like the blade of a leaf, and its Claw, which is a kind of tapering base or foot of the blade.

More commonly there is only a blade, but the petals of Roses have a very short, narrow base or claw; those of Mustard, a longer one; those of Pinks and the like, narrow claw, which is generally longer than the blade (Fig. 308).

195. A Stamen, as we have already learned (15, 17), generally consists of two parts, its Filament and its Anther.

But the filament is only a kind of footstalk, no more necessary to a stamen than a petiole is to a leaf. It is therefore sometimes very short or wanting, when the anther is sessile. The anther is the essential part. Its use, as we know, is to produce pollen.

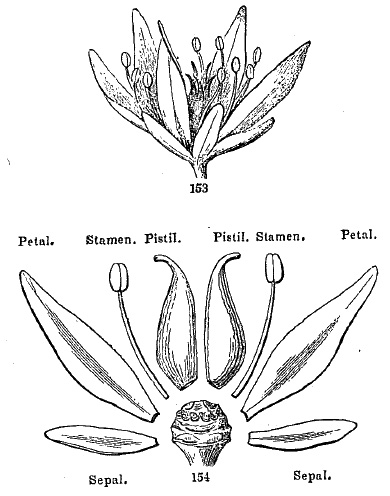

196. The Pollen is the matter, looking like dust, which is shed from the anthers when they open (Fig. 159). Here is a grain of pollen, a single particle of the fine powder shed by the anther of a Mallow, as seen highly magnified. In this plant the grains are beset with bristly points; in many plants they are smooth; and they differ greatly in appearance, size, and shape in different species, but are all just alike in the same species; so that the family a plant belongs to can often be told by seeing only a grain of its pollen.

The use of the pollen is to lodge on the stigma of the pistil, where it grows in a peculiar way, its inner coat projecting a slender thread which sinks into the pistil, somewhat as a root grows down into the ground, and reaches an ovule in the ovary, causing it in some unknown way to develop an embryo, and thereby become a seed.

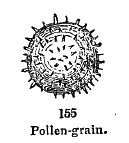

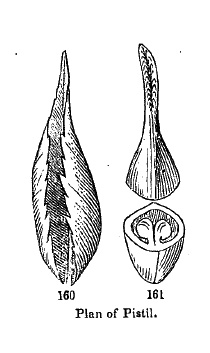

197. As to the Pistil, we have also learned that it consists of three parts, the Ovary, the Style, and the Stigma (16); that the style is not always present, being only a stalk or support for the stigma. But the two other parts are essential, the Stigma to receive the pollen, and the Ovary to contain the ovules, or bodies which are to become seeds.

Fig. 156 represents a pistil of Stonecrop, magnified; its stigma (known by the naked roughish surface) at the tip of the style; the style gradually enlarging downwards into the ovary. Here the ovary is cut in two, to show some of the ovules inside. And Fig. 157 shows one of the ovules, or future seeds, still more magnified.

198. Nature of the Flower. In the mind of a botanist, who looks at the philosophy of the thing,

A flower answers to a sort of branch. True, a flower does not bear much resemblance to a common branch; but we have seen (90-109) what remarkable forms and appearances branches, and the leaves they bear, occasionally take.

Flowers come from buds just as branches do, and spring from just the same places that branches do (169). In fact, a flower is a branch intended for a peculiar purpose. While a branch with ordinary leaves is intended for growing, and for collecting from the air and preparing or digesting food, and while such peculiar branches as tubers, bulbs, &c., are for holding prepared food for future use, a blossom is a very short and a special sort of branch, intended for the production of seed.

If the whole flower answers to a branch, then it follows that (excepting the receptacle, which is a continuation of the flower-stalk) --

The parts of the flower answer to leaves. This is plainly so with the sepals and the petals, which are commonly called the leaves of the blossom. The sepals or calyx-leaves are commonly green and leaf-like, or partly so. And the petals or corolla-leaves are leaves in shape, only more delicate in texture and in color. In many blossoms, and very plainly in a White Water-Lily, the calyx-leaves run into corolla-leaves, and the inner corolla-leaves change gradually into stamens, showing that even stamens answer to leaves.

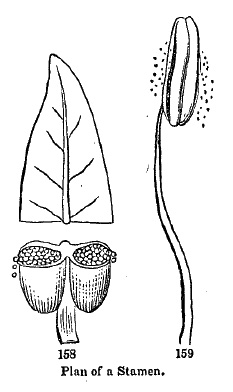

198a. How a stamen answers to a leaf, according to the botanist's idea, Fig. 158 is intended to show.

The filament or stalk of the stamen answers to the footstalk of a leaf, and the anther answers to the blade. The lower part of the figure represents a short filament, bearing an anther which has its upper half cut away, and the summit of a leaf is placed above it.

Fig. 159 is the whole stamen of a Lily put beside it for comparison. If the whole anther corresponds with the blade of a leaf, then its two cells, or halves, answer to the halves of the blade, one on each side of the midrib; the continuation of the filament, which connects the two cells (called the connective), answers to the midrib; and the anther generally opens along what answer to the margins of a leaf.

199. It is easy to see how a simple pistil answers to a leaf. A simple pistil, like one of those of the Stonecrop (Fig. 154, 156) is regarded by the botanist as if it were made by the folding up inwards of the blade of a leaf (that is, of what would have been a leaf on any branch of the common kind) so that the margins come together and join, making a hollow closed bag, which is the ovary; a tapering summit forms the style, and some part of the margins of the leaf in this, destitute of skin, becomes the stigma.

To understand this better, compare Fig. 160, representing a leaf rolled up in this way, with Fig. 156, and with Fig. 161, which are pistils, cut in two, that the interior of the ovary may be seen. It is here plain that the ovules or seeds are attached to what answers to the united margins of the leaf. The particular part or line, or whatever it may be, that the ovules or seeds are attached to, is called the Placenta.

200. Varieties or Sorts of Flowers. Now that we have learned how greatly roots, stems, and leaves vary in their forms and appearances, we should expect flowers to exhibit great variety in different species. In fact, each class and each family of plants has its flowers upon a plan of its own. But if students understand the general plan of flowers, as seen in the Morning-Glory, the Lily (Fig. 1-12), and the Stonecrop (191), they will soon learn to understand it in any or all of its diverse forms.

The principal varieties or special forms that occur among common plants will be described under the families, in the Flora which makes the Second Part of this book. There students will learn them in the easiest way, as they happen to meet with them in collecting and analyzing plants. Here we will only notice the leading Kinds of Variation in flowers, at the same time explaining some of the terms which are used in describing them.

201. Flowers consist of sepals, petals, stamens, and pistils. There may be few or many of each of these in any particular flower; these parts may be all separate, as they are in the Stonecrop; or they may be grown together, in every degree and in every conceivable way, or any one or more of the parts may be left out, as it were, or wanting altogether in a particular flower.

And the parts of the same sort may be all alike, or some may be larger or smaller than the rest, or differently shaped. Flowers may be classified into several sorts, of which the following are the principal.

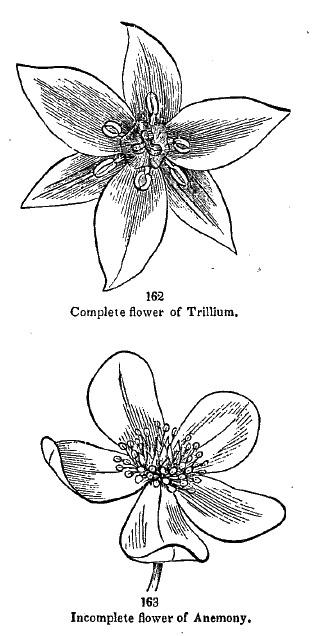

202. A Complete Flower is one which has all the four parts, namely, calyx, corolla, stamens, and pistils. This is the case in all the flowers we have yet taken for examples; also in Trillium (Fig. 138, reduced in size, and here in Fig. 162, with the blossom of the size of life, and spread open flat).

203. A Perfect Flower is one which has both stamens and pistils. A complete flower is of course a perfect one; but many flowers are perfect and not complete, as in Fig. 163, 164.

204. An Incomplete Flower is one which wants at least one of the four kinds of organs. This may happen in various ways. It may be

Apetalous, that is, having no petals.

This is the case in Anemony (Fig. 163), and Marsh-Marigold. For these have only one row of flower-leaves, and that is a calyx. The petals which are here wanting appear in some flowers very much like these, as in Buttercups (Fig. 238) and Goldthread.

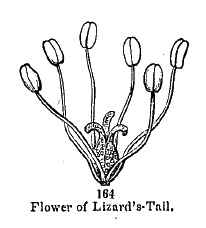

Or the flower may be still more incomplete, and

Naked, or Achlamydeous, that is, without any flower-leaves at all, neither calyx nor corolla. That is the case in the Lizard's-Tail (Fig. 164), and in Willows.

Or it may be incomplete by wanting either the stamens or the pistils; then it is

205. An Imperfect or Separated Flower. Of course, if the stamens are wanting in one kind of blossom there must be others that have them. Plants with imperfect flowers accordingly bear two sorts of blossoms, namely, one sort

Staminate or Sterile, those having stamens only, and therefore not producing seed, and the other

Pistillate or Fertile, having a pistil but no good stamens, and ripening seed only when fertilized by pollen from the sterile flowers.

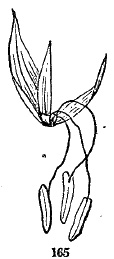

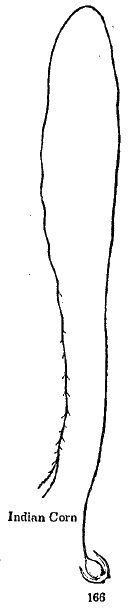

The Oak and Chestnut, Hemp, Moonseed, and Indian Corn are so. Fig. 165 is one of the staminate or sterile flowers of Indian Corn; these form the "tassel" at the top of the stem; their pollen falls upon the "silk," or styles, of the forming ear below, consisting of rows of pistillate flowers. Fig. 166 is one of these, with its very long style. The two kinds of flowers in this case are

Monoecious, that is, both borne by the same individual plant, as they are also in the Oak, Chestnut, Birch, &c. In other cases

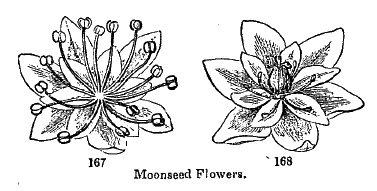

Dioecious, that is, when one tree or herb bears flowers with stamens only, and another flowers with pistils only, as in Willows and Poplars, Hemp, and Moonseed.

Fig. 167 is Moonseed a staminate flower from one plant of Moonseed, magnified; and Fig. 168, a pistillate flower, borne by a plant from a different root. There is a third way: some plants produce what are called

Polygamous flowers, that is, having some blossoms with pistils only or with stamens only, and others perfect, having both stamens and pistils, either on the same or on different individuals.

The Red Maple is a very good case of this kind; the two or three sorts of flowers looking very different when they appear in early spring, those of one tree having long red stamens and no good pistil, those of other trees having conspicuous pistils, in some blossoms with no good stamens at all, in others with short ones.

There are also what are called abortive or

206. Neutral Flowers, having neither stamens nor pistils, and so good for nothing except for show.

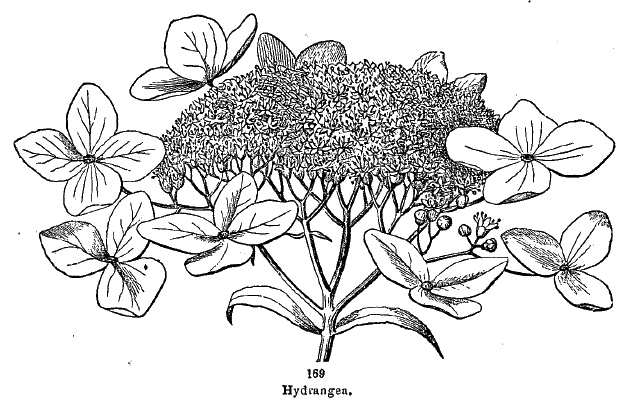

In the Snowball of the gardens and in richly cultivated Hydrangeas all the blossoms are neutral, and no fruit is formed. Even in the wild state of these shrubs, some of the blossoms around the margin of the cluster are neutral (as in the Wild Hydrangea, Fig. 169), consisting only of three or four flower-leaves, very much larger than the small perfect flowers which make up the rest of the cluster. Also what the gardener calls Double Flowers, when full, are neutral, as in double Roses and Buttercups. These are blossoms which by cultivation have all their stamens and pistils changed into petals.

207. A Symmetrical Flower is one which has an equal number of parts of each kind or in each set or row.

This is so in the Stonecrop (Fig. 153), which has five sepals in the calyx, five petals in the corolla, ten stamens (that is, two sets of stamens of five each), and five pistils. Or often it has flowers with four sepals, and then there are only four petals, eight stamens (twice four), and four pistils.

So the flower of Trillium (Fig. 162) is symmetrical; for it consists of three sepals, three petals, six stamens (one before each sepal and one before each petal), and a pistil plainly composed of three put together, having three styles or stigmas.

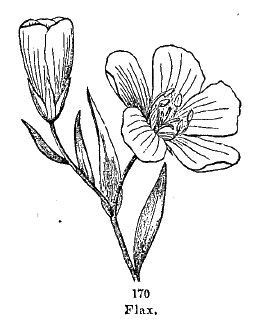

Flax affords another good illustration of symmetrical flowers (Fig. 170); it has a calyx of five sepals, a corolla of five petals, five stamens, and five styles.

In such flowers, and in blossoms generally, the parts alternate with each other; that is, the petals stand before the intervals between the sepals, the stamens, when of the same number, before the intervals between the petals, and so on.

208. An Unsymmetrical Flower is one in which the different organs or sets do not match in the number of their parts.

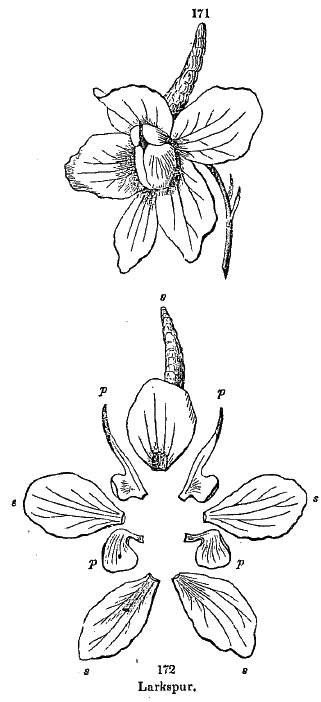

The flower of Anemony, Fig. 163, is unsymmetrical, having many more stamens and pistils than it has calyx-leaves. And the blossom of Larkspur (Fig. 171) is unsymmetrical, because, while it has five sepals or leaves in the calyx, there are only four petals or corolla-leaves, but a great many stamens, and only one, two, or three pistils.

The sepals and petals are displayed separately in Fig. 172; the five pieces marked s are the sepals; the four marked p are the petals.

209. A Regular Flower is one in which the parts of each sort are all of the same shape and size.

The flowers in Flax (Fig. 170) and in all the examples preceding it are regular. While in Larkspur and Monkshood we have not only an unsymmetrical, but

210. An Irregular Flower; that is, one in which all the parts of the same sort are not alike.

For in the Larkspur-blossom one of the sepals bears a long hollow spur or tail behind, which the four others have not; and the four small petals are of two sorts.

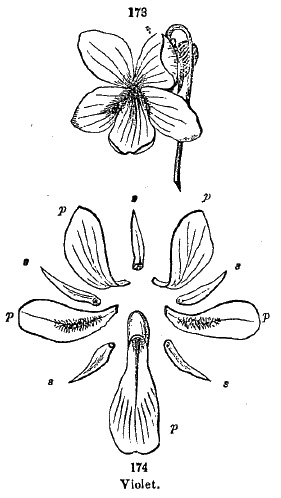

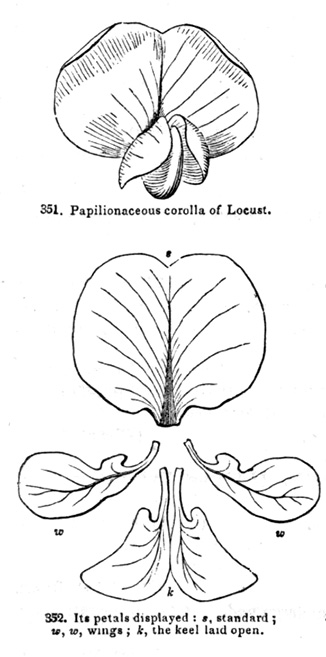

The Violet-blossom (Fig. 173) and the Pea-blossom (Fig. 351) are symmetrical (except as to the pistil), but irregular. Fig. 174 shows the calyx and the corolla of the Violet above it displayed; s, the five sepals; p, the five petals. One of the latter differs from the rest, having a sac or spur at the base, which makes the blossom irregular.

2b. Forms and Kinds of Flowers. CLICK HERE

Analysis of the Section.

191. Flowers: their parts. illustrated by the Stonecrop: 192. A pattern flower. 193. Leaves of flower or Perianth. 194. Peta1, its Blade and Claw. 195. Stamen; its parts. 196. Pollen, its structure and use. 197. Pistil, its parts. 198a. Nature of the flower; its parts answer to leaves. 198b. How a stamen answers to a leaf. 199. How a pistil answers to a leaf: Placenta.

200. Sorts of Flowers: one general plan: 201. Varied in several ways. 202. Complete flower. 203. Perfect flower. 204. Incomplete flower: apetalous, naked. 205. Imperfect or separated flowers: staminate or sterile; pistillate or fertile; monoecious, dioecious, or polygamous. 206. Neutral flowers. 207. Symmetrical flowers. 208. Unsymmetrical flowers. 209. Regular flowers. 210. Irregular flowers.